These days, paying for TV programming is a fact of life. You pay your cable company or some streaming service and the only question is do you want Apple TV and Hulu or would you rather switch one out for NetFlix? But back in the 1960s, paying for TV seemed unthinkable and was quite controversial. Cable TV systems were rare, and the airwaves were a public resource, so allowing someone to charge to watch TV on the public airwaves was hard to imagine. That was the backdrop behind the Telemeter — an early attempt to monetize TV programming that was more like a pay phone than a modern streaming service.

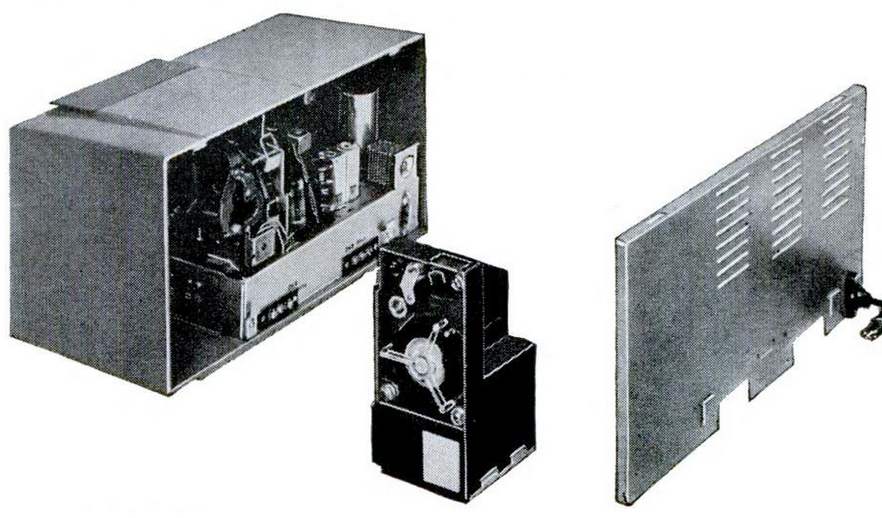

[Lothar Stern] wrote about the device in the November 1959 issue of Popular Mechanics (see page 220). The device looked like a radio that sat on top of your TV. It added a whopping three pay-TV channels, and inside was a coin box, and — no kidding — a tape punch or recorder. These three channels were carried from a Telemeter studio over what appears to be a dedicated cable strung on existing phone poles.

Of course, TVs with coin boxes were nothing new. But those TVs were found in public places, airports, and hotels. The money was simply to turn the TV on for a set amount of time. This was different. A set-top box unscrambled channels delivered over a dedicated cable. Seems like old hat today, but a revolutionary idea in 1959.

At Home

The Telemeter had a control labeled “Program Information” that played an audio description of the three programs currently available. A bypass allows the user to tune in normal free TV as well. The Telemeter itself broadcast on either channel 5 or 6, assuming one of these channels was open in your area.

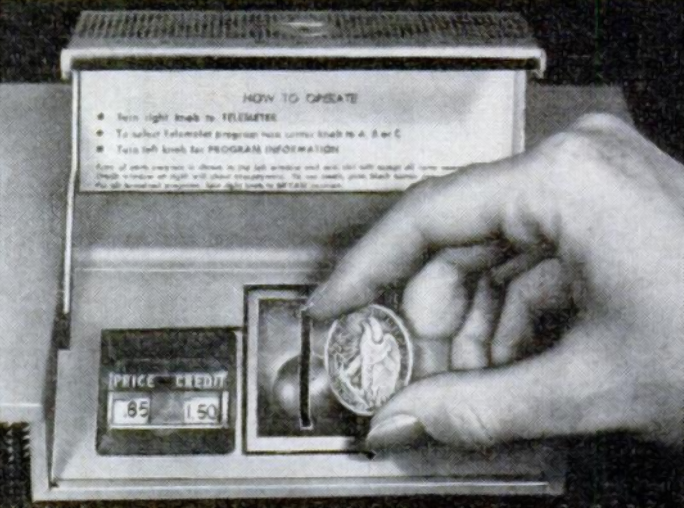

Suppose you heard that something you wanted to watch was on channel “B.” You’d turn to channel five on the TV and set the Telemeter to channel B. You’d lift a little lid on the box and find a window with the price of the program. There would also be a coin slot for you to insert your money. The box didn’t make change, but it would give you credit for excess money against future purchases.

Why a Tape?

The tape device inside wasn’t for programming. It registered what programs you’d paid for. Every month or two, someone would visit your home, empty the coin box, and switch tapes. The data on the tape told the company what shows you watched, which allowed them to pay providers and gather statistics. It also made sure the coins in the box matched the amount charged. Here you thought that companies monitoring your viewing habits was a modern thing!

At first, it might seem hard to imagine that someone would visit your home to empty out a coin box, but until recently, most electric, gas, and water services were the same way. Typically, but not always, the meters were outside your home, so they didn’t enter, but it was the same idea. Had the Telemeter caught on, it would be easy to imagine a system where your usage was on credit and the tape outside your house would generate your bill.

The practical problems of people swindling your coin acceptor — like they did with payphones — would have been an issue. Not to mention people simply hacking the device.

Business

Paramount was interested in the technology and bought 50% of the company in 1951. In 1952, they performed a brief test of their scrambling technology on the air in Los Angeles. By 1953, they had wired up a network in Palm Springs, California. Need some bar trivia? The first feature film on pay TV was Forever Female staring Ginger Rodgers and William Holden. There were 70 homes that could have watched it, and the cost was $1. One of those 70 homes, by the way, was owned by Bob Hope.

Things changed in 1954. The service had 148 users, with more waiting for service. An average subscriber was dropping $10 a month on movies. But drive-in theater owners sued, and it became hard to source movies for the fledgling service. The service shut down in 1954, but Paramount wound up owning the entire company. lt’s no surprise that movie theaters were dreadfully frightened of pay TV, but check out the theater ad below.

Back to our story. In 1959, the service was reincarnated as a Canadian company that carried on until 1965. In 1960, they connected 1,000 subscribers in Ontario. Despite adding sporting events and original movies, the service did not prosper. It peaked at 5,800 homes in the area around Etobicoke, Ontario, a suburb of Toronto, but when it ceased operation in 1965, there were only 2,500 users. At the peak, reports claim the average subscriber spent $0.80 a week (or about $1.22 a week if you exclude people who didn’t watch anything).

Cost

So, what did this modern convenience cost? The Palm Springs network charged almost $22 to install the box. A movie typically went for $1 to $1.25. The first program was a college football game that cost $1 and Telemeter claimed that 97% of users tuned into the first broadcast.

Palm Springs had an early master antenna system so residents could receive TV from Los Angeles. That was a $162 install plus $65 a year, so the $22 was not that high.

The cost was a lot less in the Canadian incarnation. According to the article, you paid $5 to have it connected, but keep in mind that $5 in 1959 was more like $50 today. That was enough to buy five gallons of milk, 20 gallons of gas, or take five people to the movies. Presumably, the company made their money by emptying your coin box every month.

The price per program was said to vary. There could be sponsored free programs, too, but you could expect those to have commercials.

Other Systems

Zenith experimented with Phonevision to deliver programming using broadcast frequencies and phone lines. That isn’t surprising since Zenith had looked into pay television as early as 1931. In 1951, some Zenith TVs had connectors for Phonevision. The system required the user to call an operator to be placed in a queue for a particular movie. When the movie was available, the set top box would receive instructions via the phone line to unscramble the movie. The bill showed up on your regular phone bill. Depending on who you asked, the system was a flop or a success. The scrambling method, however, was not compatible with color TV, so there was a definite limit to the technology.

RCA and Skiatron had Subscriber-Vision. This was similar to Phonevision, but used punched cards instead of a phone line. You’d insert the card to start decoding. A new card arrived in the mail every week. Initially, the card was a normal IBM punch card, but those were easily duplicated. Later versions used a “translucent card” with “a circuit printed in metallic ink” (that from Sponsor Magazine’s May 1952 edition).

In 1957, a famous system in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, ran briefly. It was more like a modern cable system. The service provided a descrambler for a monthly fee.

The Zenith system was as early as 1951, but all were victim to the FCC’s indecision about pay-per-view. If the FCC allowed over-the-air scrambling, it would change the landscape. If they didn’t allow it, then things like Telemeter or Phonevision would be necessary. It would be 1961 before the FCC allowed real tests and 1963 before Zenith did the first over-the-air test.

Future

Of course, cable TV systems made anything like this seem silly, and the Internet is in the process of wiping out cable TV. But this wasn’t always obvious. Even the president of Zenith TV said that it would be too expensive to wire large areas like Los Angeles or New York with cable TV.

The company behind the Telemeter, the International Telemeter Corporation, persisted as part of Paramount and its owners for a number of years and tried to create pay-per-view equipment and systems, but it was just too early. For example, they offered a box that would let cable operators accept a quarter to display cable TV for an 18-hour period. While paid services would eventually be the answer, it would arrive much too late for Telemeter to be more than a historical footnote.

There were a lot of gizmos associated with early cable TV. Everyone wants to know about the weather and cable operators were happy to oblige. Then, the weather went high-tech, at least by the standards of the day.